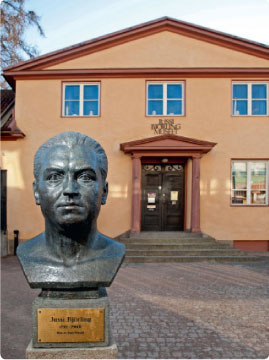

Jussi of the Month December 2019

Debut number two December 1930

In an earlier “Jussi of the Month” I told how Jussi Björling took his first steps in front of an audience on an operatic stage at the Stockholm Opera in July 1930. I also explained the custom of three debuts, and how it was unique that a 19½-year-old pupil of the Opera School was already considered ready for a debut. The first one was on 20 August 1930 as Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni, given under the name of Don Juan. Of course it was “the boss”, the Opera’s general manager and Jussi’s teacher John Forsell, who took that rash decision.

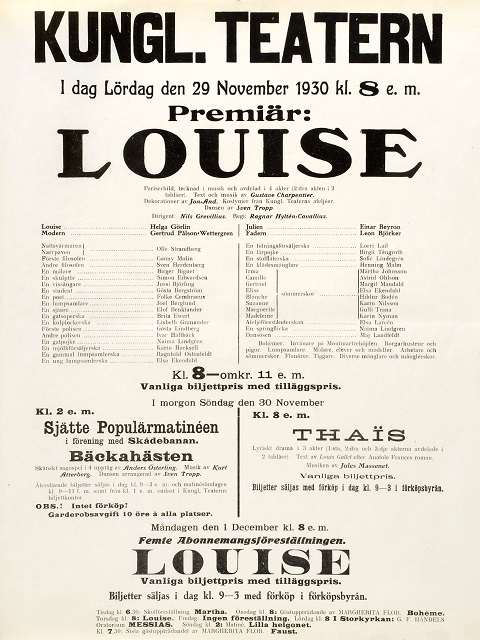

Click here to enlarge the image

to the left and lists 36 singers – a major part of the ensemble – so even the student and opera stipendiary Mr Björling was needed.

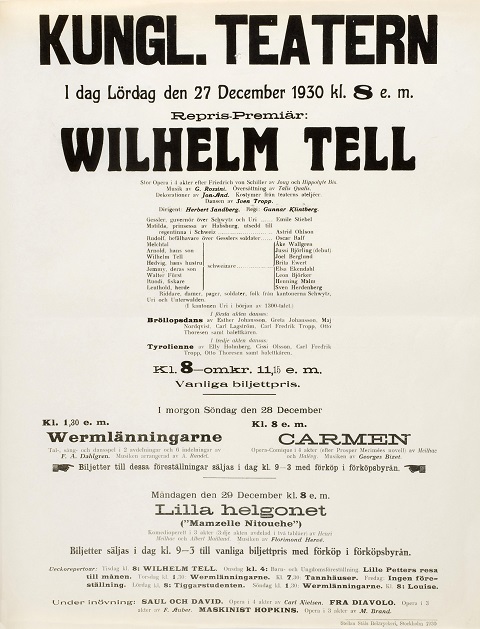

During this period Jussi prepared for his second debut: something quite different and even more challenging. Don Ottavio may be a long role, but most of it is safely in the middle register. Even though Mozart’s music requires much from musicians, most singers find it friendly for the voice. Now it was time for Rossini’s Guillaume Tell (played in Swedish as Wilhelm Tell) which received its ”Replay-Premiere” 27 December 1930 and then was played eight times until spring – a success for those days. Then there were two follow-up performances during the season 1931/32. Jussi sang the tenor hero Arnold in all of them. After that, Guillaume Tell only returned to the Stockholm Opera for the season 1967/68

Click here to enlarge the image

are told that “decorations” were new (by the signature Jon-And), while the costumes “from the theatre’s ateliers” may not all have been newly made. Now a director is mentioned: Gunnar Klintberg (1870–1936) who for some years did several productions at the Opera and had the title of “first stage director”. We can guess that it was a totally traditional production. Klintberg had attended the school of the Royal Dramatic Theatre in the 1890s, and after finishing his own career as an actor he was now functioning as a director.

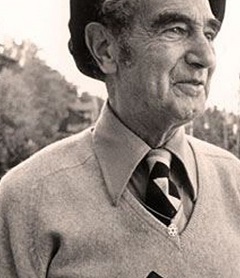

We will come back to how much renewal there may have been on the musical side. But all leading parts were newly cast and considerably rejuvenated. The conductor was also new: 28-year old Herbert Sandberg who with one small interruption would remain with the Stockholm Opera until his death in 1966, from 1946 as Court Conductor. He had come to the Opera from Berlin where he had been an assistant conductor, in particular to Leo Blech. Blech was the chief conductor at several among Berlin’s opera houses, most enduringly at the Court and later State Opera, and from 1925 he was a frequent guest conductor in Stockholm. Intrigues in Berlin, probably anti-Semitic, gave him ample time for the Stockholm Royal Opera, and John Forsell who knew him well grasped at the opportunity. Blech made a big impression from the very beginning, and Sandberg came here on his recommendation, later married Blech’s daughter, and had a lasting importance on the Stockholm Opera’s development. By the time for the Guillaume Tell premiere Sandberg had been there for two years but already conducted about 25 works during almost 200 performances. We may guess that he was ambitious when he had now been assigned a newly studied production that was even labelled a premiere, but also that his experience from how Tell was done in Germany would influence him – there it was still a repertory work.

Moses Pergament

Jussi, Joel Berglund and Leon Björker 27 December 1930

Jussi as Arnold 27 December 1930

lower alternatives, or just delete passages. Few listeners were so acquainted with the opera that they would notice the difference, except for memories how local singers had handled the part more than a decade ago. Only the most important arias were available on records, to which few people had access. Those who had happened to see Tell outside Sweden on their travels would hardly remember details, and if they did it was certainly regarded as normal that Stockholm would not always measure up to international standards. And cuts and simplifications existed also in Berlin and Paris. Those who could read the music themselves would find that French grand opéra was especially maltreated in repertoire performances, as their length and high demands had led to simplifications almost since they were new. Wilhelm Tell like Meyerbeer’s operas were seen as old-fashioned and modernizations as welcome. Dagens Nyheter’s reviewer claims that its conspiracy scene “could have benefitted from shortening”.

Actually we know that Guillaume Tell was considerably cut. Some day a researcher may investigate this in the Royal Opera’s archives, where performance materials and production notes should exist. While waiting for that we can study the playbill for Guillaume Tell the 27 December 1930 on the Internet. We find that the performance was expected to last 3 hours and 15 minutes. When we come to the next performance the timing is five minutes less, and by the third performance only three hours. This included intervals. A complete performance without intermissions lasts about four hours!

This is the sound of Jussi some month after the second debut:

De Curtis "Carmela" recorded 1931-02-11

A. Ödmann's "Tantis Serenad" ("Månstrålar klara") recorded 1931-02-11

When Guillaume Tell returned in 1967 I was a young enthusiast who saw it twice and recorded the radio broadcast. That production is described in the archive as lasting three hours “with two longer and one shorter interval”. The music time of the broadcast is roughly 2 hours and 15 minutes. I spoke to Kåge Strömbäck, at the time well-known winner in Kvitt eller dubbelt, one of Swedish Television’s first successes that followed a US model (The $64,000 Question – the money was much less in Sweden). His topic was Verdi, but he was knowledgable about earlier Italian opera and I said how happy I was to have seen Guillaume Tell. “Well, at least 48% of it!” he said – he had counted bars when following the broadcast with the piano score. I happened to look down into the orchestra pit and notice that the violin parts looked ancient, with pages sown together when longer passages were deleted. So I guess the performance materials were the same as in 1930, maybe even from the 19th century. If we go further back in the archive on the net we see that performances of this opera in the 1860s were expected to last 3 hours and 45 minutes, but in those days intervals may have been three and longer. Cuts were expected and common, and with the repertoire system not so easy to change. In 1930 it seems unlikely that the young conductor or the even younger tenor would question them and prolong a night at the opera that was already a fairly long evening.

In 1967 the entire scene for the tenor in the last act "Asile héréditaire” (maybe better known in Italian as ”O muto asil del pianto”) was cut, also of course its allegro later part. But there are sufficient challenges in the first-act duet and trio, which are totally necessary for the story. “Oh Mathilde!” (which Berg in his review calls an aria) is the tenor’s start to that duet, and in its original pitch it requires first a B flat and then when it is repeated a high C – one of many in this opera.

So of course we have to admire Jussi, but not immediately equate his ordeal with what a present-day tenor singing Arnold may have to endure. If Jussi really, as one reviewer says, was indisposed on the first night there may have been further changes. But still the achievement was phenomenal but could have threatened his vocal survival. In addition to the Tell performances he took part in four other operas during the next few months, one of them – Saul og David – his third debut role which we will deal with in “Jussi of the Month” for January 1931. He often sang twice a week, sometimes on two consecutive days – once three days in a row! To this comes appearances outside the Opera. For instance, on the two days preceding his first Arnold he sang major parts of Messiah for a broadcast and his small part in Louise.

Newspapers from December 1930 also tell us that at the end of the autumn term Mr Björling finished the Music Conservatory and was awarded its jeton or medal, and that he at this time was coming into demand as a concert artist. From January 1931 he was no longer a student but a Royal Opera stipendiary, and as we have already seen he is charged with several operas at the same time as this employment includes studying more parts which are new for him. In February he is 20 and already busy. Forsell liked to talk of his employees using the French term “sujets” – subjects! I’ll come back about his third debut next month…

Nils-Göran Olve

There is no recording by Jussi from Guillaume Tell but we can listen to Nicolai Gedda in ”Oh Mathilde” from a complete recording 1973:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMciTmZAR18.

The only commercial record of Jussi Björling in music of Rossini is the tenor aria "Cujus animam" from Stabat mater, which in its original 78 rpm issue was coupled with Ingemisco from Verdi's Requiem. The Rossini aria includes one of the highest notes Jussi recorded: a D flat, half a note higher than tenors' "high C". So at this time (1938) he had conquered his full register.

Listen to "Cujus animam" from 1938

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary