Jussi of the Month October 2020

October 1938: L’africaine, and more

On the surface, Jussi Björling’s month of October 1938 resembled most other months since he became a member of the Royal Stockholm Opera’s ensemble in 1930: a new role, a number of performances at its home base at Gustav Adolf’s square, some elsewhere, and a gramophone session. Business as usual for a full-time employee, with walking-distance home, and with long-time colleagues. After returning from his debut at the Metropolitan in New York on 24 November there would be a similar period in February–April. But by then he would have become recognized as an international celebrity, and he would make his final appearances as an employee of the Stockholm Opera.

Ten years had passed since his audition with John Forsell in August 1928, followed by the start of his studies in Stockholm. For the now 27-year old Jussi, October 1938 signified the end of ten years learning his craft with the Royal Opera as his base. An era had reached its end. The previous winter he had been to USA for the first time as a grown-up, and the success of two performances with the Chicago Opera and in concerts had led to the contract with the Metropolitan. Coming home from the US in February 1938 he had resigned from the Stockholm Opera and now was to work freelance, although he was still employed for the season 1938/39 with leave of absence November through January for his US engagement.

Autumn had begun rather normally. After an initial Aida on 11 August there followed eight other performances with the Opera during the next month. Until Anna-Lisa and he had to pack their suitcases at the end of October, that month contained:

- Vasco da Gama in Meyerbeer’s L’africaine – a new role in a new production which he did six times 4–17 October. Jussi then never sang it again, with exception for the wellknown aria ”O paradiso”.

- A gramophone recording of two arias, plus two which were not approved. This took place on 12 October, between two of his performances at the Opera (11 and 14 October).

- Taking part in the Opera’s guest performance at Västerås Theatre of Faust 20 October

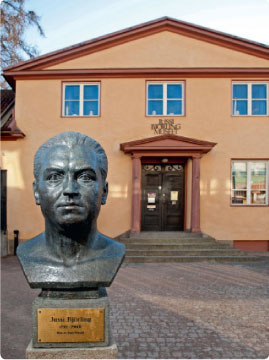

Director Harry Stangenberg talks to Jussi ahead of the October 4 premiere of L’africaine

This represented a fairly calm schedule compared to his past decade with the Opera, but there must have been several things to think about and prepare for America, although his agent Helmer Enwall and his wife Anna-Lisa handled practical matters. Three weeks after the Västerås performance he would have a broadcast concert in Detroit, his first American appearance this time. Anna-Lisa was to join him on his journey, although they expected a second child and son Anders therefore would have to make do with the company of his maternal grandmother at home at Nybrogatan 34. The couple counted on being back long before their next child was expected.

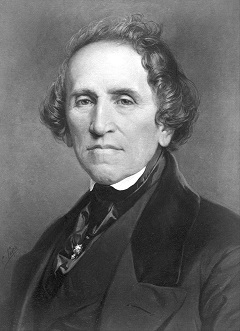

Giacomo Meyerbeer

had been one of the Stockholm Opera’s trump cards in the old opera house, where it received 167 performances 1867–88. To judge from descriptions the stage technology, which famously showed a ship being wrecked, impressed more than the opera as such. Now it was exactly 50 years since anyone had seen Afrikanskan. This was the final season for the Opera’s chief manager John Forsell, and evidently he wanted to try anew some works which had been popular in his youth. The six performances with Jussi Björling were followed by four more with Set Svanholm after Jussi had left for the US, and these have remained the final Meyerbeer performances by the Stockholm Opera. Parts of Le prophète were staged at the Vasan theatre in 1999, but discounting those performances no Swedish stage has dared to perform Meyerbeer again.

In other countries however his works have started to be played again. This is partly due to curiosity: how could something so popular just disappear? Meyerbeer was a Jew with career in Italy, France, and his native Germany. His works can be characterized as entertainment on the grandest scale, but with serious intentions. From around the turn of the century 1900 increasing nationalism, antisemitism and a general scepticism against artists who want to woe their audiences, his works came to be regarded as obsolete. In October 1938, half a year after Nazi Germany’s “Anschluss” of Austria, it had become impossible to perform L’africaine even in countries where it had used to be given occasionally, like in Vienna the year before. Even with less racial prejudice Meyerbeer had already become rarer in France and the US, and following some few productions in the 1930s he would disappear until long after WW2 – like in Stockholm.

In spite of some attempts since the 1970s, a Meyerbeer renaissance has proved difficult to get going, compared with how baroque opera, Donizetti or Berlioz, who all were out of fashion in the interwar period, have made a comeback. So why not Meyerbeer? His main operas juxtapose different cultures and describe people who are playthings of destiny in broad ethnic-political conflicts, and therefore would seem to have renewed relevance in today’s world. Meyerbeer rewrote them repeatedly in order to mobilize the optimal resources of the theatres where he was working, in particular in Paris, and he employed all the new technical tools that became available during his life (1791–1864).

And, to reverse the question: why Meyerbeer in Stockholm precisely in 1938 – when he was hardly played anywhere else, and considering the lack of success for his Huguenots ten years earlier? Was it just Forsell’s nostalgia that explained L’africaine’s return to Stockholm following fifty years of absence? The Royal Opera’s general plan for the season reminds us that Meyerbeer’s “grand historic-romantic opera used to belong to our Opera’s permanent repertoire”. Maybe the intention was to give older audience members grand opéra of a type which already had become neglected. Another explanation may be that this actually was a kind of manifesto against political events. Kurt Bendix who conducted L’africaine was Jewish, as were several others among the Royal Opera’s artistic leadership. Axel Rundberg in Svensk operakonst [The Art of Opera in Sweden]” (1952) speaks of an “old and dusty” opera that in spite of good stage direction “would not run and had to be cancelled”. But ten performances in three months was not a bad run in those days, so the question rather is why this entirely new production never returned.

Meyerbeer not only requires huge resources, his works also are difficult to give convincing scenic and musical shape. In 1938 major parts of L’africaine were cut. Stage bills announced a playing time of three hours and a quarter, and probably two intervals were included in this. At least three hours of music are probably necessary to make it justice. The first Stockholm performances in 1867 were announced to last four hours, including two 20-minute breaks. It is uncommonly difficult to tell how long L’africaine should be, as Meyerbeer did not live to complete his opera. What was performed in 1938 was a cut version of what had been performed in Paris the year after his death. The composer’s habit was to revise until the last minute, and there is a lot of extra material, so the posthumous edition which was performed and published by others may not represent his wishes. From 2013 a version which aims to be more respectful of Meyerbeer’s intentions has been given under the name Vasco da Gama. If performed in full, just the music of this lasts four hours and a quarter.

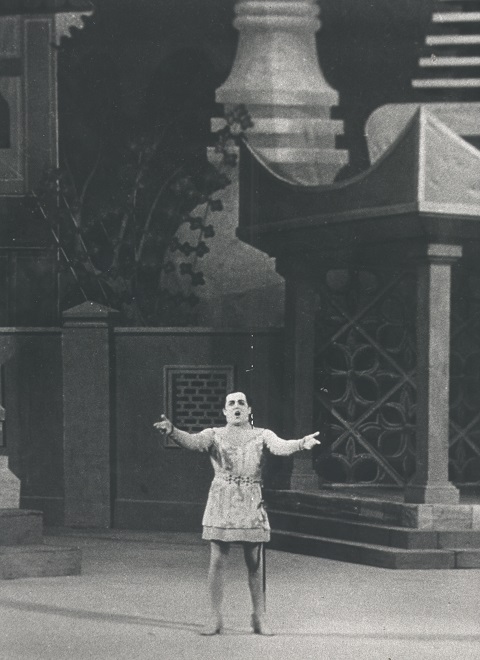

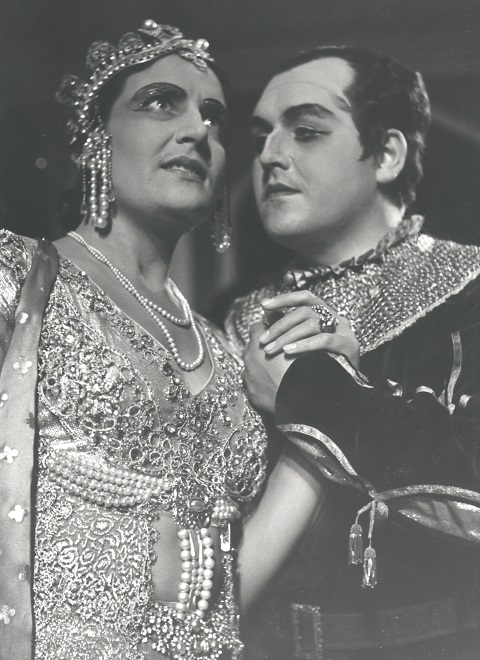

In front of the temples from L’africaine 4 October 1938

Vasco would be Jussi Björling’s final new part for a very long time. When he came back in 1939 he sang for the last time in Fanal, La traviata and Madama Butterfly. In addition to these, and during his annual guest appearances for his remaining life, his repertoire was limited to ten to twelve opera. Among these only Des Grieux in Manon Lescaut was new (in Stockholm from 1951). Stockholm audiences were never to hear his Don Carlo, his other new role on stage, which he sang in the US starting in 1950. I’ve always been struck by the contrast with his 1930s at the Opera, when during his nine seasons as permanently employed, he sang more than fifty parts, among which there were about thirty leading roles. Some he sang just a few times, like L‘africaine’s Vasco da Gama. Yet it represents a transition in the barely 28-year old singer’s life: from constant renewal as an employee to a world tenor who is content with repeating the well known.

Inez Köhler and Jussi in L’africaine October 4, 1938

Kajsa Rootzén in Svenska Dagbladet devotes much space to explaining why Afrikanskan is a really bad opera and certainly not

worth reviving. She praises the production as such, although the wrecking of the ship will not impress audiences who have watched greater wonders in the cinema. “Jussi Björling was radiant vocally, but dramatically he could not do much with Vasco who is drawn in pale colours.” Next day the same newspaper had found a visitor who had also experienced the old production fifty years earlier. He finds the male roles better performed now, particularly the “euphonious” Jussi Björling.

Cartoon of Jussi as Vasco da Gama October 4

We can form our own opinion on this, because Jussi had recorded the opera’s best-known number already one year earlier on one of

his best-selling records. He sings it in Italian as “O paradiso” and would continue to use it as a concert item. In addition to the HMV 78 with Nils Grevillius conducting from 4 September 1937 there exists half a dozen preserved recordings: one for RCA Victor in the US, the others from live concerts. Stephen Hastings in The Björling Sound prefers Jussi’s first recording: ”one of the best ever made, for the unalloyed lyricism of his sound mirrors the uncontaminated luxuriance of the setting” – that is, the exotic beauty of his environment which in his aria he compares to paradise.

The disc (HMV DB 3302) was only the second large (30cm = 12-inch) 78 rpm record Jussi made, with the aria from La Gioconda on the reverse side. He now had an international record contract which involved no longer recording his arias in Swedish. L’africaine of course is a French opera, sung in Stockholm in Swedish like almost everything in those days. In other countries as well, operas were translated into the local languages. But the main market for the record was the British commonwealth and America, where Meyerbeer’s operas were performed in Italian if at all. This had been the custom ever since they arrived there in the 19th century. Caruso and Gigli had recorded the aria in Italian, so for Jussi this language probably was a natural choice, as it did much later for Del Monaco, Di Stefano and Bergonzi.

In October 1938 it was now time for the fourth international Björling 78, a coupling of two oratorio arias: ”Ingemisco” from Verdi’s Requiem and ”Cujus animam” from Rossini’s Stabat mater. Like “O paradiso” they belong among his very best recordings. The session on October 12 was held, like always during this period, in what is now the Grünewald room of the Stockholm Concert Hall, with Nils Grevillius conducting.

Nowadays we probably listen more often to Jussi Björling’s ”Ingemisco” from the sunmmer of 1960 in the complete recording with Fritz Reiner as conductor. But Hastings finds the 78 recording to be his finest, and says that no one ever sang it better. In addition to these two versions of ”Ingemisco” there are six more with Jussi: two more of the complete Requiem and four separate ones, so already the competition from Jussi himself is strong.

The disc’s reverse side, ”Cujus animam”, never achieved the same popularity. Many find it hard to understand what this up-beat song has to do in an oratorio about Christ’s mother by the Cross. But it is possible to hear sighing in the intense singing, and we should of course remember the continuation of Easter: the happy message that this sacrifice will benefit mankind. The aria had been recorded by Enrico Caruso in 1913 and Beniamino Gigli in 1932, and their records were also published in Europe by HMV whose new star tenor Jussi had just become. Maybe that contributed to the idea that this aria was a suitable coupling for “Ingemisco”.

”Cujus animam” culminates in a cadenza whose highest note is a D flat, a half-tone higher than a ”high C”. Gigli did not attempt it, and Rossini probably expected his soloist to use half-voice or falsetto to reach it. In Jussi’s first take the note was not a total success, but that recording has been available in spite of this. In the one we normally hear there are no obvious difficulties, although this may be the highest note he had reason to sing in public. A Swedish writer who did not approve even of Jussi’s D flat was Carl Bruun, who in his book Att samla grammofonskivor [To collect gramophone records] (1950) meant that “no man of woman born has yet avoided a squeaking sound like that of a rubber pig, bought in an outdoor market." Still he thought that “Björling does his utmost in this passage, and as a whole the record is one of his best, particularly for the reverse ‘Ingemisco’.”

Together with the two issued items the two arias from the third act of Il trovatore were attempted but not approved. Jussi later recorded them in July 1939, with good results. But test pressings from 12 October 1938 remain and have been issued on a Bluebell CD.

Before we take leave of October 1938 it is interesting to note that Jussi Björling’s final operatic performance before his Met debut took place on 20 October in Västerås, a town a little more than 100 km west of Stockholm. At the time the Royal Stockholm Opera took its production on “Riksteatern” tours to other Swedish towns. A playbill for Bohème in Gothenburg by the Royal Opera on 30 October announces Jussi Björling as Rodolfo, but Einar Beyron substituted for him so Faust in Västerås turned out to be Jussi’s final Swedish performance for the time being. The Opera’s leading artists, chorus, orchestra and even ballet took part, which seems incredible in a theatre now seating 399! It had been newly renovated and this was its reopening. According to Stockholms-Tidningen Jussi thought that it was “a little heavy to sing in. It is hard to tell why, but you feel it strongly. Apart from that it is of course a nice theatre following its rebuilding.” They probably could take a special train home after the performance.

Contemporary photo of the "heavy" salon in Västerås Theater

At the Met his audience would be almost ten times larger – and yet there were rarely complaints about the acoustics. But that is another story, which you can read about in Jussi of the Month from September 2013. That was the first article in this long series, and it focuses on November 1938 and Jussi’s Met debut!

Nils-Göran Olve